Holsinger Studio Photo Editing

by Julia Munro

Cite This Entry

- APA Citation: Munro, J.F. (2022, May 9). Holsinger Studio Photo Editing. Holsinger Portrait Project. https://juel.iath.virginia.edu/node/2065

- MLA Citation: Munro, Julia F. "Holsinger Studio Photo Editing." Holsinger Portrait Project. Univ. Virginia (2022, May 9). Web. [Date accessed].

Return to Main Page, List of African American Individuals.

Manipulation of Lighting

The lighting in the room while a photograph was taken, the retouching done to a negative, how light or dark the photo prints, and even the type of paper used in printing all had effect on the perceived lightness of the subject photographed, something that was of particular significance when photographing African Americans. Because nearly all of the Holsinger images in the UVA Library collection are of the actual glass plate negatives rather than printed images, we cannot make assertions about how the final print product appeared; the negatives themselves, however, show variations in shade and other alterations that are important to evaluate.

The manipulation of lighting in the studio and alterations done to the negative and/or the print product were actions that of course happened when photographing anyone or anything; from the outset of commerical photography, newspaper articles, technical manuals, and even advertisements address how important a consistent and plentiful lighting source is to the quality of the final product, and advise viewers in the colors to wear so as not to appear washed out or murky. In western Europe and North America, (Britain, France, and the United States primarily), the average customer was caucasian or light-skinned; hence, a darker-colored customer would inevitably require especial attention, if only for the fact that the typical lighting would not provide a successful image (one in which the facial features are clearly delineated). This would certainly have been the case for Holsinger, as the catalogue of his images suggest: of the approximately 11,000, approximately 600 are of African Americans (a more accurate percentage would be to consider of the total portraits taken by Holsinger, how many were of African Americans).

By the 1900s, it was certainly inexpensive enough that nearly everyone could and did have their photo taken at a studio and, in the South, Holsinger's studio was typical in having both black and white customers (there were not segregated studios per se. Arguably some studios were preferred over others for African American customers; some studios were run or owned by African Americans in the larger cities; and some customers may have chosen to visit itinerant photographers, some of which were African American, i.e. Mangus). Holsinger did have a long-time African American employee, Horace Porter (who presumably operated the camera at times as well assisting with the studio setting, the development of the negatives, etc.). While there is no evidence to suggest that Holsinger was favored over other studios by African American customers - indeed, in this regard as in all others he seemed to be a typical, average studio (although having the distinction of certainly being the most well-known or "first name" studio in town), it is interesting to note that in later years, when run by his son Ralph W. Holsinger, the studio did gain a reputation for being "unfriendly" to African Americans). Regardless, the typical American photographer would have had experience photographing dark and light skin, although with varying success (as with any aspect of photography, a photographer would gain a reputation for being more skilled than others) and, it certainly may have been the case that African American customers would have had to settle for an image that turned out "good enough." Consider for instance W. E. B. DuBois's observations in 1923: "the average white photographer does not know how to deal with colored skins and having neither sense of their delicate beauty of tone nor will to learn, he makes a horrible botch of portraying them. From the South especially the pictures that come to us, with few exceptions, make the heart ache" - hence DuBois's assertion that young African Americans ought to consider a career in photography ("Photography" 249-50).

The two portraits of Luella Bray below show adjustments in brightness to balance between the white dress and the darker-toned skin of the subject:

Luella Bray (X24603A) June 9, 1911

Luella Bray (H24603A), June 9, 1911

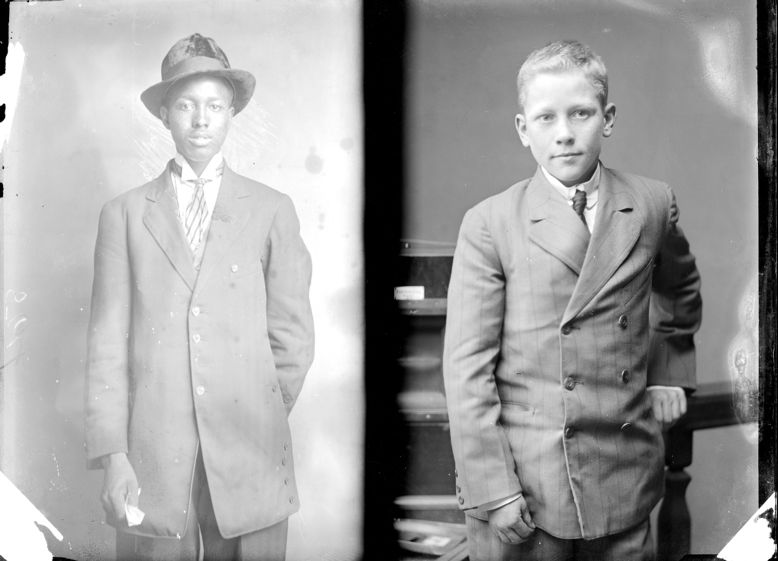

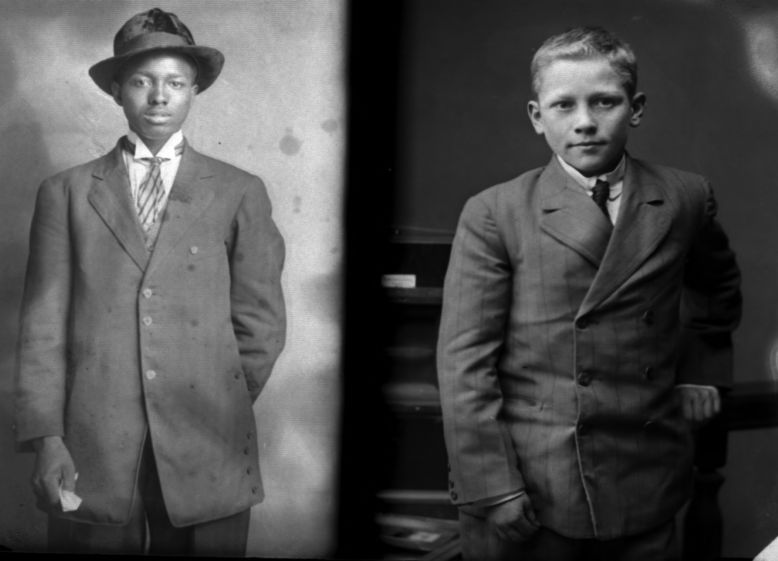

Similarly, the below two photos (Untitled, December 7, 1912) are an excellent example of the differing levels of lighting needed to properly delineate the facial features of the boys (X00859A):

Untitled December 7, 1912 (X0859A2):

Photographic Retouching

Retouching or editing the negative in order to produce a more pleasing photographic print was quite common in portrait photography in this time period. The photographer would use pencils and ink to cover up portions of the image, or actually scratch the glass plate itself to affect the final product (erasing stray hairs, for example, or darkening or lightening areas of the figures). Some examples of retouching in Holsinger's collection are as follows.

The photograph below of Cornelia Howard, for example, appears to show some light, circular abrasians over the face. Photographers would do this by, "mildly abrading the surface of the emulsion [on the glass plate itself] with an exfoliant such as powdered chalk or cuttlefish, which was commonly used" ("The Art of Retouching" para. 10). It appears to have been done to better delineate the subject's face; it was also done when producing vignette prints (see "Will Berger" below for an example of a vignette-style framing of a portrait).

Howard, Cornelia 1914-10-02 (X02647A)

Another portrait showing a similar abrasion over the face is the March 22, 1913 portrait of Patsy Jones (X01368A). Note the large markings over the left portion of the plate are damage and were not intentional:

Additionally, the below photograph of Amanda Williams (X02577A), taken 1914-09-05, also shows this distinct circular abrasian:

Sadie Jones, 1918-06-22, X06382A

Granville Cooper, 1918-12-30 X07239A

Another type of retouching done to the negatives was applying ink or paint to cover over portions of the image. The photographer might paint over the background, for example, to "blot it out" so that only the person appears. In Holsinger's photos, he appears to have done this in order to "delete" or "erase" portions of the image. These appear as white "blots" in the finished print image, since the print is the reverse of the negative (which would have had the paint or ink applied directly to its surface).

The below image, "Mrs. Hugh Davis," is the perfect example of this type of retouching. Here, Holsinger has "removed" the nanny's hands, which were steadying the baby, so that the whole figure of the baby can be seen. Note that he did not bother covering over or "removing" the nanny entirely, since that portion of the image would not have been printed in the final product.

Mrs. Hugh Davis, December 22, 1914 (X02920A):

Below shows a very clear image of the cloth adjustable "shades" seen in many of the photos (Untitled, no date H18563A)

Sources

"The Art of Retouching - Pre-Photoshop" The Past on Glass & Other Stories, November 28, 1917.

Du Bois, W. E. B. “Photography,” The Crisis. 26: no. 6 (October 1923): 249.

"The Holsinger Studio Collection." Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Accessed 13 September 2019.