Virginia’s Geography and Demographics, 1819-1861

by Ian Iverson

The following post is part of a new series which seeks to contextualize the personal papers uploaded to JUEL. This work will attempt to synthesize the work of prominent historians to illustrate the dynamism and conflict which defined Jefferson’s University between 1819 and 1861.

Many Americans still mistakenly associate life in pre-Civil War Virginia with the “moonlight-and- magnolias” romanticism promoted by Confederate apologetics like Gone with the Wind. Even as textbooks have shifted to a more critical interpretation, many high school students still receive a monolithic impression of the slave-holding South. While we should all applaud the renewed focus on the horrors of slavery, we must also work to disaggregate the experiences typical of the enslaved and slaveholders of the deep South’s blackbelt from the more varied experiences within Upper South states like Virginia. For example, despite the significance of “King Cotton” in the broader American economy, Virginia’s agricultural staples throughout the period consisted of tobacco, grain, and pork. The Virginia Jefferson knew during his retirement in the 1820s was very different from the state which debated the merits of secession in the spring of 1861. The following posts will narrate the social, political, economical, and cultural transformations of this era, paying special attention to the ways in which the University of Virginia and those associated with it shaped and were shaped by these changes.

Virginia’s Geography and Demographics, 1819-1861

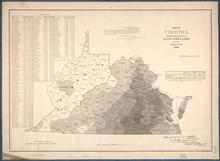

Antebellum Virginia consisted of five distinct geographic regions: the Tidewater, Piedmont, Shenandoah Valley, Southwest, and Trans-Appalachian Northwest. Scholars disagree on the exact boundaries of each region, but the map above of Virginia’s enslaved population in 1860 highlights one of the central distinctions between the the densely enslaved Eastern regions and the sparsely enslaved Western zone. This uneven distribution of enslaved people would lead to diverging courses of economic development and distinct political cultures. The implications of these differences will be discussed in detail in future posts. This piece simply seeks to lay out changes in Virginia’s demography between the founding of the University in 1819 and the secession crisis of 1861.

Settled by the English in the early seventeenth century, the costal Tidewater had served as the center of Virginian power for more than a century and half. By the time of the American Revolution, however, decades of soil-exhausting tobacco production had taken their toll. The erosion in the region’s agricultural output in the decades after the American Revolution mirrored a shift in political power as the state’s capital moved from Williamsburg to Richmond. Nevertheless, because the state constitution of 1776 awarded seats in the legislature on the basis of counties, rather than population, and the 1830 constitution’s system of districts did not provide a means of reapportioning representatives, the geographically compact Tidewater retained a disproportionate political influence until the passage of the “reform” constitution of 1851. Throughout the antebellum period, Tidewater planters proved among the most politically conservative voices in the state, ardently defending slavery, states rights, and the elitist assumptions of classical republicanism.[1]

The Piedmont, which stretched between the costal counties and the Blue Ridge Mountains, replaced the Tidewater as the state’s premier agricultural region in the late eighteenth century. Despite the area’s natural fertility, declining yields and a drop in the global price of tobacco led many planters, including Thomas Jefferson, to transition to grain crops like wheat and corn, a pattern which accelerated rapidly in the 1820s. These two regions combined formed the East, the heart of Virginia’s plantation economy. Demographically dominated by enslaved laborers, Eastern planters jealously guarded their political privileges and largely opposed Western efforts to further democratize the Old Dominion. The vast majority of the University of Virginia’s students came from the East throughout this period.[2]

The three Western regions: the Shenandoah Valley, the Southwest, and the Trans-Allegheny Northwest drew thousands of new settlers over the course of four decades. Growing at an astonishing rate relative to the Eastern counties, the West expanded from 44 percent of the state’s white population in 1820 to 60 percent by 1860. The Valley’s rich soil transformed these middle counties into the state’s breadbasket where small farms cultivated lush fields of grain with a combination of enslaved and free labor. Although enslaved people made up only 17 percent of Valley’s population in 1860, as compared to nearly 50 percent in the Piedmont and over 40 percent in the Tidewater, slaveholders retained the confidence of the area’s nonslaveholding population, thanks in part to their willingness to rent-out slaves and thus broaden the number of ordinary whites invested in this coercive institution.[3]

The Southwest emerged as the state’s poorest region. With a large population of landless and illiterate whites, a small number of planters retained political influence despite directly controlling only 10 percent of the population as slaves. Connected by ties of kinship and common interest to Eastern planters, the Southwests local elites tended to cooperate with the East on issues concerning slavery. [4]

Finally, the Trans-Allegheny Northwest region emerged as the state’s odd duck. The Trans-Allegheny’s demographics more closely resembled its free-state neighbors Ohio and Pennsylvania then any of Virginia’s other regions and its close ties to the Ohio River Valley shaped its economic development. Thus while Virginia as a whole remained a “slave society,” this Trans-Allegheny zone developed into “a society with slaves.”As described by the distinguished historian Ira Berlin, within a slave society “slavery stood at the center of economic production” whereas in societies with slaves “slavery was just one form of labor among many” and “slaves were marginal to the central productive process.” With barely three percent of the region’s population enslaved in 1860, Trans-Allegheny leaders felt only marginally invested in the “peculiar institution.”[5]

Alongside these regional distinctions, the growth of cities in Virginia, most notably Richmond, Norfolk, and Petersburg added an additional level of demographic complexity unknown to Jefferson and his contemporaries. Virginia’s gradual turn towards industrialization will be discussed in a later post, but urban environments created unique challenges for Virginia’s slaveholding elite as enslaved workers mingled alongside free people of color and immigrant laborers in under-supervised workshops, factories, and working-class neighborhoods.

In a trend which disturbed some Virginia planters even as they filled their pockets, the Old Dominion took on a growing role in the domestic slave. Virginia’s enslaved population grew rapidly through natural increase throughout the nineteenth century, providing many masters with a healthy “surplus” of laborers amid the state’s agricultural transformation. Coinciding with the rapid westward expansion of the burgeoning “Cotton Kingdom” in the Old Southwest (consisting of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Western Tennessee, and Louisiana), Virginia planters sold enslaved people to new owners in the West or gave them to their children as they migrated to the Cotton States. As a result, while Virginia’s enslaved population had expanded rapidly between 1790-1830 from 293,000 to nearly 470,000, exports to the Cotton States in the succeeding decades minimized growth so that the Old Dominion’s enslaved population remained under 500,000 at the start of the Civil War.[6] This trend, along with the practice of “hiring out” enslaved laborers to an outside employer— increasingly engaged in non-agricultural pursuits such as manufacturing, mining, and international commerce— strained the paternalist conception of slavery cultivated by the institution’s most adamant champions in Virginia.[7]

Scholars often classify Virginia as an Upper South State alongside North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas, but a brief glance at the map above reveals Virginia’s unique regional position.[8] To the south lay two decidedly Southern States: Tennessee and North Carolina, who’s enslaved populations in 1860 sandwiched Virginia’s 31 percent at 25 percent and 33 percent respectively. To the west and northeast were two border states: Kentucky and Maryland, who’s enslaved populations totaled 20 percent and 13 percent respectively, as well as the slaveholding District of Columbia, where only 4.2 percent of the population was enslaved. Finally, and crucially for the state’s Trans-Allegheny northwest, Virginia also bordered the free states of Pennsylvania and Ohio.[9] As a result, we might achieve a more accurate understanding of antebellum Virginia adopt the framework of the UVA trained historian William A. Link and consider Virginia a border state. Indeed, the subsequently partition of the state into staunchly Confederate Virginia (consisting of the Tidewater, Piedmont, Valley, and Southwest) and Unionist West Virginia (the Trans-Allegheny Region) during the Civil War lends further credence to this alternative framing.[10]

While the University attracted an increasing number of students from across the South, the Virginian students at UVA, always a majority of the student body, came overwhelmingly from the Tidewater, Piedmont, and—to a lesser extent— Valley counties. The impoverished Southwest and culturally distinct Trans-Allegheny remained virtually unrepresented. UVA’s faculty primarily hailed from the Eastern region of the state and many had received their own educations locally at either UVA or William & Mary. As a result, the University, chartered for the benefit of the entire state, remained a distinctly regional institution.

1. Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2013), 14-19; William W. Freehling, The Road To Disunion, Volume 1: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 170-171; William G. Shade, Democratizing the Old Dominion: Virginia and the Second Party System, 1824-1861 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996), 50-51. Classical republicanism insisted that only economically independent men of virtue could govern responsibly. As a result, proponents of classical republicanism in Antebellum Virginia insisted that voting and officeholding should to be limited to propertied and well-educated white men.

2. William Blair, Virginia’s Private War: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 1861-1865 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 13. Shade, Democratizing the Old Dominion, 44-45.

3. Shade, Democratizing the Old Dominion, 18-22; William A. Link, Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003) ProQuest Ebook Central, 18-19, 45.

4. Link, Roots of Secession, 45.

5. Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998), 8-9. Link, Roots of Secession, 45.

6. Shade, Democratizing the Old Dominion, 518; 1860 U.S. Census, Population by Color and Condition, 518.

7. Link, Roots of Secession, 44; The nature of patriarchy and paternalism in the antebellum South remains hotly contested among historians. Although nearly a half-century old, Eugene D. Genovese’s Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Pantheon, 1974) remains the definitive work on the subject. For more a recent discussion of paternalism see Lacy Ford “Reconfiguring the Old South: ‘Solving’ the Problem of Slavery, 1787-1838,” The Journal of American History 95 (Jun. 2008), 95-122, esp. 109-118.

8. Freehling, Road to Disunion I, 131. Blair, Virginia’s Private War, 30.

9. 1860 U.S. Census, Population by Color and Condition, 181, 214, 359, 467, 518, 588.

10. Link, Roots of Secession, 18.