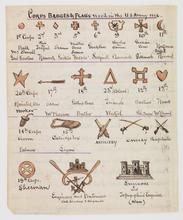

A Brief Guide to Civil War Armies

by Ian Iverson

The organization of the Northern and Southern armies confuses many students of the Civil War, both because the complexity of nineteenth-century military structure and naming conventions which allowed for forces on opposite sides of the conflict to share (or at least appear to share) a name. The following guide seeks serves as a roadmap through the labyrinth of Civil War nomenclature.

Branches of the Army

Infantry: By far the most common branch of the service, between 75-80 percent of soliders on each side were in the infantry. The infantry fought on foot and marched from point to point in-between battles. The typical soldier was armed with a rifled-musket (although many carried older smoothbore muskets early in the war) and a bayonet and fought in mass formations across open fields or, increasingly as the war went on, large systems of dug-in fortifications.

Cavalry: Often regarded as the most glamorous branch, a minority of men in each army— somewhere between 15-20 percent— fought as mounted troopers. While traditionally trained to fight on horseback, Civil War cavalry increasingly fought dismounted and employed their mounts to move quickly across the countryside. They served as the army’s “eyes and ears,” scouting terrain and enemy positions and deploying to attack enemy supply trains or overwhelm isolated units on the periphery of a battlefield. Typical cavalry weapons included carbines, pistols, and sabres.

Artillery: The smallest combat branch of each army, between 5-6 percent of soldiers manned the cannons which delivered ferocious barrages of shot, shell, and canister during major engagements. Most were designated as “light artillery” and manned mobile cannons and mortars mounted on wheels. A few units, designated as “heavy artillery” regiments actually fought as infantrymen, but had received training in firing large caliber fixed-position guns, such as those that protected Washington, D.C. throughout the war.

Engineers: A small corps of specially trained army engineers worked to construct and repair roads, bridges, and fortifications throughout the conflict. In the pre-war U.S. army, many highly-respected officers, including Robert E. Lee, served as engineers thanks to the specialized training they received at West Point.

Medical: Army physicians were commissioned officers with previous medical training. A typical regiment included a surgeon and assistant surgeon who cared for sick men in the unit and were deployed to field hospitals during and immediately after battles. Larger army hospitals could be found in cities and towns with large public buildings. In fact, the University of Virginia served as a Confederate military hospital for most of the conflict.

Other common designations for types of units included:

A. Sharpshooters: A small number of Union-soldiers received designated training as marksmen. Usually attached to support a regular infantry unit, companies of U.S. sharpshooters carried the rapid-firing and highly accurate Sharps rifle and wore distinct forrest-green uniforms.

B. Dragoons: An obsolete branch of the army which traveled on horseback but fought on foot. In 1861, the last two regiments of U.S. dragoons were redesignated as cavalry, reflecting the changes in tactics which had altered the fighting style of the latter branch.

C. Zouaves: soldiers uniformed in the colorful costume developed by French soldiers in North Africa.

D. Rifles: In earlier conflicts where most soldiers had carried smoothbore muskets, some small units were designated to carry more-accurate (but harder to load and fire) rifles. The adoption of the rifled-musket had made such designations obsolete, but some units adopted the designation for the sake of tradition.

E. Lancers: A handful of cavalry units were initially armed with lances (spears) along with pistols to encourage close-quarter fighting on horseback. A failed experiment, most of the lancers were soon re-armed with carbines.

Units (by size)

Company: Usually recruited from a single locality, companies in theory consisted of 80-100 men but by mid-war had usually been reduced to 30-40 due to casualties, disease, and desertion. A company was commanded by a captain, who was often, though not always, elected by the men. Ten companies, lettered A-K (excluding J), made up a regiment.

Battery: The standard artillery unit, batteries consisted of four to six cannons and was commanded by a captain. Some batteries formed into regiments while others operated as “independent batteries” within a brigade.

Battalion: An atypical unit size more common in the cavalry, a battalion was made up of 5-6 companies and was usually commanded by a captain or major.

Regiment: Theoretically made up of ten full companies (1,000 men), most regiments in the field during the war had been reduced to less than 500 strong. Commanded by a colonel or lieutenant colonel, regiments were organized by the individual states and were numbered in the order of their recruitment: i.e. 1st Virginia Cavalry, 7th North Carolina Infantry, 12th New York Light Artillery.

Brigade: A group of four to six regiments commanded by either a senior colonel or a brigadier general.

Division: A group of three to five brigades commanded by a brigadier or major general. The Confederate Army tended to have larger Divisions and fewer Corps.

Corps: Two or more divisions commanded by either a major general (Union) or a Lieutenant General (Confederate).

Army: Two or more corps commanded by either a major general (Union) or a full general (Confederate).* Each army was responsible for combatting the enemy within a particular geographical region.

*The only Union officer to receive a promotion to a rank higher than major general during the Civil War was Ulysses S. Grant who was promoted to Lieutenant General in 1864 and given command of all Union armies.

Names of the Armies

Civil War armies followed distinct naming conventions tended to name their forces after major bodies of water, especially rivers or after wider geographic regions. Opposing armies operating in a theater sometimes unintentionally shared a name, such as the Union Army of the Tennessee (named after the Tennessee River) and the Confederate Army of Tennessee (named after the state).

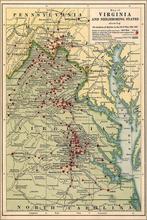

The principal armies operating in Virginia during the Civil War were:

Confederate:

The Army of the Shenandoah (1861 — commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston)

The Army of the Potomac (1861 — commanded by General P.G.T. Beauregard)

The Army of the Kanwana (1861 — commanded by Brigadier General Henry A. Wise and Brigadier General John B. Floyd)

The Army of the Northwest (1861 — commanded by Brigadier General Robert S. Garnett)

The Army of the Peninsula (1861-1862 — commanded by Major General John B. Magruder)

The Army of Northern Virginia (1861-1865 — commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston and General Robert E. Lee)

The Army of the Valley (1864-1865 — commanded by Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early)

Union:

The Army of Northeastern Virginia (1861 — Commanded by Major General Irwin McDowell)

The Army of Virginia (1862 — Commanded by Major General John Pope)

The Army of the Potomac (1861-1865 — Commanded by Major General George B. McClellan, Major General Ambrose B. Burnside, Major General Joseph Hooker, Major General George Gordon Meade, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant [de facto])

The Army of the James (1864-1865 — Commanded by Major General Benjamin F. Butler and Major General Edward Ord)

The Army of the Shenandoah (1864-1865 — Commanded by Major General Phillip P. Sheridan)

Names of Battles

Civil War battles often received two names, one Northern and one Southern. Union forces tended to name battles after a notable landscape feature on the battlefield (a hill, river, etc.) whereas the Confederates usually adopted the name of the nearest town or man-made structure. However, as with all rules, there are some exceptions. Some examples from battles in Virginia are listed below.

Union Name/Confederate Name

Bull Run/Manassas, July 21, 1861

Ball’s Bluff/Leesburg, October 21, 1861

Fair Oakes/Seven Pines, May 31 – June 1, 1862

Beaver’s Damn/Mechanicsville, June 26, 1862

Chickahominy River/Gaines’s Mill, June 27, 1862

Second Bull Run/Second Manassas, August 29–30, 1862

Chantilly/Ox Hill, September 1, 1862

Opequon/Winchester, September 19, 1864

For further inforrmation please visit UVA's Nau Center for Civil War History at http://naucenter.as.virginia.edu