Virginia and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861

by Ian Iverson

As sectional tensions rose to a crescendo in the aftermath of John Brown’s 1859 raid on the Federal Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginians fiercely debated what steps they should take to protect their interests. Many especially former Whigs, such as UVA Law Professor John B. Minor, continued to defend the virtues of the Union and insisted that the Commonwealth’s interest in slaves was safer inside the United States than outside of it. Virginia had long served as a production center for the domestic slave trade, a market which might collapse should a Southern Confederacy re-open the African slave trade. In addition, under the U.S. Constitution, Virginians were guaranteed the return of any fugitive slaves who escaped to nearby free states. Outside of the Union, such protections would collapse and in the case of civil war, figures such as Minor presciently predicted that Virginia would become the fiercest battleground. As a result, Virginian Unionsists like Minor rallied behind the Constitutional Union Party, led by John Bell of Tennessee, and sought compromise which would maintain both the Union and slavery. Although Bell won the Old Dominion’s electoral votes, Republican Abraham Lincoln secured victory handily through his Northern majority, an outcome which precipitated the secession of the Deep South.

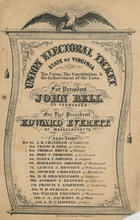

With this tension in the air, Virginia’s Southern rights radicals, Union-minded moderates, and all of those in-between directed their focus to the presidential contest of 1860. A four-way race, the election pitted Republican Abraham Lincoln against the Northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, the Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge, and the Constitutional Union Candidate John Bell. Lincoln, running a on a platform opposed to slavery’s further extension, received just under 2,000 votes in Virginia (a little more than one percent of the state-wide vote), clustered almost exclusively in the four counties of the Northwest panhandle. The other three candidates proved more competitive. The Democratic vote, split nationally between Breckinridge, a proponent of a Federal Slave Code, and Stephen A. Douglas, the champion of ‘popular sovereignty’ on the slavery question both retained supporters in Virginia. While most Virginia Democrats backed the Southern-rights candidate, several yeomen dominated counties in the Shenandoah Valley voted for Douglas— giving him just under 10 percent of the total vote while awarding 44.5 percent to Breckinridge. Such a division among the Democrats allowed the ex-Whigs, now known simply as the Opposition, to rally a plurality of 44.6 percent for John Bell— an aging statesman from Tennessee who had run a platform of sectional compromise and conciliation within the Union.[1]

Despite winning only forty percent of the popular vote, Lincoln’s sweep of the North granted him an electoral college majority and elevated him to the White House. This result prompted the lower South, starting with South Carolina, to adopt ordinances of secession rather than live under a Republican president. White Virginians now faced the decision of following their fellow slaveholders out of the Union or holding out in the hope of brokering a compromise between the North and Deep South. The generational divide that had emerged in the late 1850s hardened among Virginians east of the Alleghenies. While students at UVA voiced support for the new Southern Confederacy, urged on by recent alumni and a handful of States’ Rights professors like Albert T. Bledsoe, most faculty remained resolutely opposed to any action until the Border States could gather a peace convention. John B. Minor denounced the rashness of “rabid South Carolinians” and urged a “last appeal to the North” to avoid the “fratricidal strife” that would plunge the country into ruin and blood.[2]

A similar pattern emerged among white Virginia women. Mary Blackford, a cousin of John B. Minor, had long urged sectional reconciliation and moderation on the slavery question as an active member of the American Colonization Society. Her generation had long sought to serve as mediators between the sections, embarking on projects with Northern women such as the preservation of Washington’s Mount Vernon to poster good will. In early 1861 she wrote that the thought of seeing her five sons arrayed against the Star Spangled Banner caused her “a sorrow that made me feel that the grave is only place for me.” Younger women, especially those who had spent time in the Lower South, like Kate Virginia Cox Logan, caught the secessionist fever early and fervently expressed their hope for a quick withdrawal from the Union. Such women wore blue cockades to demonstrate their support for Southern rights as they packed the gallery of the state capitol building at Richmond to in an attempt to influence the debate of the state’s secession convention.[3]

Virginians at first appeared to favor a conservative course. While the state legislature authorized a convention to consider secession, the election for delegates on February 3rd gave self-identified Unionists a substantial majority. Furthermore, in a separate provision, voters mandated that the convention submit any resolutions back to the people for ratification. Assembling at Richmond on February 13th after the secession of the seven Deep South states, the delegates divided themselves into three camps.

Around a third favored immediate secession in solidarity with the Deep South. Mostly from Eastern counties with large enslaved populations, the secessionists insisted that Virginians could no longer trust the Federal government to protect their slave property. One of Albemarle County’s delegates, James P. Holcombe, a UVA law Professor and fervent defender of slavery, identified with this faction.

Of the Unionists, perhaps one-in-five were Unconditional Unionists, committed to maintaining the nation at any cost. Almost exclusively from the Trans-Allegheny region, these delegates brought their traditional Western hostility to the planter class and a keen awareness of their region’s economic integration with the free states.

The remaining Unionists, almost half of the total convention, were conditional Unionists. Self-identified moderates, these delegates reflected the views of men like John B. Minor who hoped that Congress or a national convention might yet compromise and reconstruct the Union. These delegates recognized a state’s right to secede, but felt they could not justify withdrawing from the Union until the Lincoln administration committed an overtly unconstitutional act against either slavery or the seceded states. Their reluctance to join hands with the Deep South become clear upon a bit of reflection. Virginia had long served as a production center for the domestic slave trade, a market that might collapse should a Southern Confederacy re-open the African slave trade. In addition, under the U.S. Constitution, Virginians were guaranteed the return of any fugitive slaves who escaped to nearby free states. Outside of the Union, such protections would collapse and in the case of civil war, most recognized that Virginia would become the fiercest battleground. Still, they announced quite clearly that they would not tolerate any attempt by the Federal Government to coerce the seceded states back into the Union.[4]

Amid the uncertainty in the weeks immediately preceding following Lincoln’s inauguration, the convention adopted a wait-and-see approach. Many put their hopes in the efforts of Kentucky Senator John J. Crittenden to broker a compromise through a series of constitutional amendments that would have permanently protected slavery from Federal interference. A month after Lincoln’s inauguration, on April 4th, the body voted against adopting a secession resolution but chose to remain in session in case circumstances were to change suddenly.

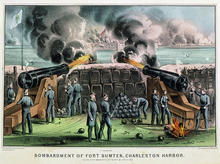

At this same moment, a stand-off in Charleston harbor between secessionist militia and federal troops stationed at Fort Sumter reached its climax. Unwilling to acknowledge South Carolina’s independence from the United States, President Lincoln refused to evacuate Fort Sumter’s garrison and instead determined to resupply the Fort with food and other provisions, though not with arms or munitions, to preserve this symbol of Federal authority. South Carolnians and the new President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, could not stand for such an affront to their independence and opened fire on the Fort on the morning of April 12, 1861. While Sumter’s batteries returned fire for several hours, the outnumbered and outgunned U.S. troops quickly realized the futility of the fight and surrendered to Confederate forces that same afternoon before suffering any casualties.[5]

The bombardment, while bloodless, ignited war fever in both the North and South. Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the Southern rebellion forced the eight slave states who had thus far remained in the Union (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee) to choose sides.

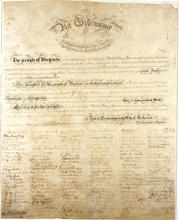

For Virginia’s conditional Unionists, Lincoln’s call for troops represented the sort of coercion they had sworn to oppose. Thus, on April 17, the convention reversed itself and voted Virginia out of the Union by a margin of 88-55. The day before, former Governor Henry Wise had, ironically, ordered the seizure of same the Federal Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in a reversal of the 1859 raid by John Brown. Virginia’s voters would subsequently ratify the Ordinance of Secession by an overwhelming in a popular vote held in May. Many of the state’s Trans-Allegheny citizens, horrified by the result, vowed to oppose the Eastern secessionists at any cost.[6]

Many popular accounts of Virginia’s secession continue to confuse the nature of Unionism in Eastern Virginia and Virginians’ motivation to support the Southern Cause after Fort Sumter. In apologetic accounts, prominent figures such as Robert E. Lee were opposed to both slavery and secession and sided with the Confederacy only out of loyalty to Virginia herself. Such a narrative distorts the motivations of late-blooming Confederates and erases tens of thousands of Virginians, free and enslaved, white and black, who remained loyal to the Union. Figures such as Mary Blackford’s son, Charles Minor Blackford, and conditional Unionist delegate Jubal Early, eagerly joined the Confederate Army out of a desire to preserve slavery in the face of perceived Northern aggression. During the secession debate they had sought to preserve slavery through the political mechanisms the Union, but when Northern arms appeared to threaten the South’s peculiar institutions, they became as determined Confederates as any South Carolinian Fire Eater. Indeed, thousands of white Virginians would enthusiastically and unapologetically make war on the popularly elected government of the United States to defend the institution of slavery from the existential threat posed by the Lincoln administration.

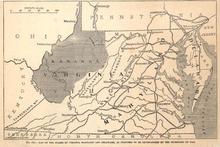

But this narrative does not tell the whole story of Virginia. Thousands of enslaved Virginians seized the opportunity offered by the war to undermine their masters. Thousands of black Virginians, among them 240 from Albemarle County, would eventually serve in Union ranks, including 18 previously owned by the decedents of Thomas Jefferson. Meanwhile, in the immediate aftermath of secession, white unconditional Unionists from the Trans-Allegheny Northwest gathered at Wheeling, in Ohio County, to reject the Confederacy and declare their continued allegiance to the United States. Led by figures now largely forgotten, such as Francis H. Pierpont, their actions laid the groundwork for the new state of West Virginia, which would enter the Union with a Free State constitution in 1863. Indeed, the fact that dozens of Virginia counties rejected the Confederacy is often forgotten on this side of the Alleghenies. Moving forward, we must continue to grapple as Virginians with this mixed legacy of America’s bloodiest and most divisive war.[7]

1. For Virginian reactions to John Brown’s Raid see Peter S. Carmichael, The Last Generation: Young Virginians in Peace, War, and Reunion (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 117; Elizabeth R. Varon, We Mean to Be Counted: White Women and Politics in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 138-140; William A. Link, Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003)188-189; William W. Freehling, The Road To Disunion, Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 213-215.

2. For an overview of the Virginians views of the election of 1860 see Link, Roots of Secession, 190-213.

3. John B Minor to Mary Lancelot Minor, January 14, 1861, The Papers of John B. Minor, University of Virginia Special Collections Library; Daniel W. Crofts, Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 122-125;

Link, Roots of Secession, 217-223.

4. Varon, We Mean to Be Counted, 152-153.

5. For concise accounts of Virginia’s secession debate see Freehling, The Road To Disunion, Volume II, 501-515; Edward L. Ayers, In the Presence of Mine Enemies: The Civil War in the Heart of America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003), 119-142.

10 William J. Cooper, We Have the War Upon Us: The Onset of the Civil War, November 1860-April 1861 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012), 263-270.

6. Carmichael, The Last Generation, 143; Link, Roots of Secession, 244-248.

7. William R. Kurtz, “Black Virginians in Blue,” John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History: University of Virginia, Accessed July 2, 2019. http://naucenter.as.virginia.edu/tags/black-virginians-blue; William A. Link, “‘This Bastard New Virginia’: Slavery, West Virginia Exceptionalism, and the Secession Crisis.” West Virginia History, New Series, Vol. 3, no. 1 (Spring 2009), pp. 37-56.