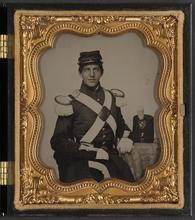

James Ancrum Winslow: UVA Unionist

by Ian Iverson

Born in 1839 to one of New England’s oldest families, James Ancrum Winslow’s background as a “Boston Brahmin” made him an unlikely fit for the distinctly southern University of Virginia. Nevertheless, after attending the Roxbury Latin Academy and Harvard University, where he graduated with a master’s degree in 1859, Winslow chose to journey South pursue his law degree.[1] Although his father, Commander John Ancrum Winslow of the U.S. Navy, sympathized with abolitionism, by studying under the direction of John B. Minor and James P. Holcombe, Winslow would have been exposed to the period’s most elaborate legal defenses of slavery. Arriving on grounds in the fall of 1859, shortly before John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry brought the sectional crisis to new heights, Winslow seems to have thrived in his new setting. Earning the respect of his peers and forming a close bond with Professor Minor and his family, Winslow returned for the 1860-1861 academic year despite the tension of the 1860 presidential contest. Only after Lincoln’s election and the secession of the Lower South did Winslow contemplate leaving the University. Writing to his daughter Mary in January 1861, Professor Minor reported that Winslow had “seemed much cast down of late” and expressed “little to ground hope upon” despite his continued popularity with his fellow students.[2]

Winslow withdrew from the University following Virginia’s secession in April and traveled home to Boston. Upon his arrival, he took time to write back to Professor Minor, expressing his surprise at the North’s unanimous support for war. Having spent the previous two years seeking to clarify the North’s position to Southerners, he now struggled to do the reverse. Winslow expressed his dismay at how “newspapers on both sides are full of error, & falsehood.” Trying to explain the situation in Massachusetts, Winslow could only reflect, “Everything is the counterpart of what you see at the South” and glumly pronounce that “there is no end to the mis-statements on both sides.”[3]

It appears that like Professor Minor, James A. Winslow had hoped that the Union could be maintained through peaceful compromise. Frustrated by what he perceived as radicalism and intransigence on both sides, he lamented the coming of the Civil War. Still, with the advent of hostilities, Winslow threw his support behind the Union cause. In the course of the conflict, two of his brothers served as officers in the Union Navy while his father rose to the rank of commodore by sinking the famed Confederate Commerce Raider C.S.S. Alabama in 1864. [4] Winslow himself remained in Boston, serving as a private in the 4th Battalion of Massachusetts Infantry and later as a first lieutenant in Company I of the 2nd Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. Relieving regular troops to go to the front, the Massachusetts militiamen garrisoned Boston Harbor’s fortifications and guarded Confederate prisoners of war at Fort Warren.[5] Practicing law in Boston while off-duty, Winslow grew to support President Lincoln and emancipation, campaigning vigorously for the Union Party ticket in 1864.[6] After the war, Winslow moved to Binghamton, New York where he practiced law and became active in the local literary scene. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the combination of his Southern friendships and wartime service, Winslow’s only surviving reflection on the conflict, a Decoration Day poem published by the Binghamton Republican offered a reconciliationist narrative which simultaneously trumpeted the Union while honoring soldiers on both sides.

“Our brothers once, our brothers now,/ If erring true and brave,/Our kinsmen, children of the land/ Our soldiers fought to save./Unreckoned blood, uncounted gold,/Hateful fraternal strife/It cost to bring our brothers back./And save the nation’s life.”[7]

1. Quinquennial Catalogue of the Officers and Graduates of Harvard University, 1636-1895 (Cambridge, Mass.: The University Press, 1895), 170; History of Littleton, New Hampshire, George C. Furber, ed., Vol. 3 (Cambridge, Mass.: The University Press, 1905), 534-535.

2. Journals of the Chairman of the Faculty for Session 36, 1859 - 1860. Journals of the Chairman of the Faculty for Session 37, 1860 - 1861. John B. Minor to Mary L. Minor, January 14, 1861, Letters of John B. Minor: Jefferson’s University the Early Life, http://juel.iath.virginia.edu/node/114?doc=/db/JUEL/letters/Minor John_B_Minor_to_Mary_L_Minor_January_14_1861_Transcript.xml&key=P39142#m1.

3. James Ancrum Winslow to John B. Minor, May 21, 1861, Letters of John B. Minor: Jefferson’s University the Early Life, http://juel.iath.virginia.edu/node/114?doc=/db/JUEL/letters/Minor/James_Winslow_to_John_B_Minor_May_21_1861_Transcript.xml&key=P39142#m1.

4. John M. Ellicot, The Life of John Ancrum Winslow, Rear-Admiral, United States Navy (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1905), 7.

5. Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines in the Civil War: Compiled and Published by the Adjutant General, Vol. 5 (Northwood, Mass.: Northwood Press, 1932), 331; “Military Affairs,” Boston Daily Advertiser, February 27, 1865; Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (Boston: William White, 1865).

6. “Enthusiastic Union Rallies in Cambridge, Roxbury, Winchester, and Other Places,” Boston Daily Advertiser, November 5, 1864.

7. “From the Republican, Binghamton, New York.,” The Troy Messenger (Troy, Alabama), July 1, 1875.