A Bond Created in Bondage

by Evelyn Reece

John Minor, a respected professor and local political advocate in the mid-1800s, carried an ambiguous and often conflicting view on the institution of slavery. Publicly, Minor denounced slavery, a judgment which many revered as a disgrace to his Southern heritage. Despite criticism, Minor aided in the passage of Charlottesville resolutions that reviled Virginia’s legality of servitude as a “social and political evil.” Unfortunately, Minor was unable to translate his beliefs into actions at home. The benefits of unpaid labor outweighed his morality as he continuously enslaved and “rented” both adults and children on his property, even separating family on occasion. He used his status and wealth to help perpetuate the institution rather than suspend it; however, one enslaved person, Scott Wood, appeared abnormally thankful to have John Minor as a master.

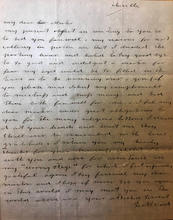

In a letter received on January 2, 1854, Scott Wood constructs a tearful farewell to his master, describing his “true gratitude” in being able to serve John Minor. Wood writes, “I dreaded the parting hour and hated to say good bye to so good and so indulgent a master for fear my eyes would be so filled with tears as to be running over.” This unusually emotional sentiment is backed only modestly with examples of Minor’s “indulgence. For instance, Minor once writes Wood’s original owner, Benjamin Wood, in July of 1853 in order to approve a summer trip for Scott. He does not agree to pay for his servitude during that summer, however, he is “quite willing for Scott to be gratified,” and believes it may be beneficial to his health. Additionally, Minor provided “religious lessons” to many of his slaves. These Sunday school sessions led Scott to draft the following: “I feel my dear master under great obligation to you for the many religious lessons I received at your hands...I hope if I never see you again in this world I may meet you in the world above.” Other citations and letters outline a similar spiritual role and conscience of Minor.

Despite these few and far between appeasements, Minor rarely aided or freed slaves. He sustained his personal practice of buying and hiring enslaved persons until the end of the Civil War, submitting many to the horrors of hard labor, desitute living conditions, punishments, and so forth. The appearently sincere bond under bondage between Minor and Wood is rare and intriguing, yet can likely be attributed to the vast disparity in power in their relationship. Similar to the modern Stockholm syndrome, feelings of trust or affection can arise by a victim, or slave, toward their captor, or master. These sentiments are often considered coping mechanisms in light of the dangerous or appalling situations endured by the victims. The systematic abuse and enslavement of Wood likely tolled on his psychological welfare, leading him to overly idolize John Minor; additionally, it remains a possibility that Minor was substantially “kinder” to Scott than his previous owners, providing Scott with false sentiments of gratitude.