Water at the University of Virginia from 1825-1850

by Meghan Ellwood

Jefferson built his university to be a “temptation to the youths of other states to come, and drink of the cup of knowledge.”[1] While knowledge has always been abundant to quench the academic thirst of students, water has not been abundant and available to quench their physical thirst. Supplying the water necessary for cooking, drinking, bathing, and farming was particularly challenging in the rural and secluded town of Charlottesville, Virginia, where Jefferson laid his University. Securing a reliable and convenient source of water for the University of Virginia presented a logistical and financial challenge from the very beginning. The University made both major and minor endeavors to secure a direct and consistent water source over the course of its first twenty-five years. Understanding the system for supplying water offers a more detailed understanding of the quality of life for students and professors at the University, as well as communication between the faculty and Board of Visitors during its early period.

Before the state legitimately chartered the University of Virginia in 1819, it was known as Central College. However, on February 26, 1819, the Board of Visitors of Central College formally became the Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia, and subsequently all the land previously owned by the college became land of the University of Virginia. [2] During this period, resources the land provided determined if life was sustainable. Therefore, the University was forced to rely on natural water sources present on the land. The University’s land included two distinct plots (Figure 1).[3] The first plot included 153 acres of woodland and a small mountain intended for an observatory, and the second plot was roughly 92 ½ acres and would be used for the site of the main University. Separating the two sections owned by the University was a 132-acre plot owned by Mr. John Perry. Unfortunately, water was scarce on the land available to the University.

Figure 1: Lands of Central College, 1819. Depicting 153-acre plot (left) and 92-½ acre plot (right). Original in Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

The Board of Visitors of the new University of Virginia then had the logistical task of finding water where natural resources were limited (Figure 2).[4] There were probably close to two hundred people living on Grounds in 1825, including professors and respective families, 123 students, and numerous enslaved men, women, and children; all were using water for drinking, bathing, cooking, and supporting livestock.[5] While the Rivanna River could have supplied a large enough water source, it was located over three miles away, not close enough for the University to take advantage of. The Board had three remaining options for water supply: the collection of rainwater, building reservoirs near springs, and tapping into streams from the surrounding mountains. The plan devised took advantage of all three sources. Sheets of tin covered the roofs of Hotels and Pavilions so that rainwater could be collected and stored in cisterns, some of which were as large as 6,500 gallons (although it is unlikely that every cistern remained full at all times). Other cisterns held water brought in from natural springs and streams on “neighboring highlands” from the University’s western side with wooden pipes.[6]

Figure 2: Green and Peyton Map of Albemarle County, 1875. Including water sources surrounding the University. Four springs mentioned by Dinsmoore between two plats of the University’s land circled in red.

The springs were the primary source of water, but the University only had access to the one on University Mountain. There were four other “bold strong springs,” described in a letter from James Dinsmore and John Perry to the Board of Visitors.[7] These springs were located on the strip of land between the two plots that made up the campus, which the University did not own (Figure 2). Mr. Perry himself owned the land, but whether he was willing to let the University tap into his springs with their wooden pipeline is unclear. Nevertheless, the University desperately needed access to the springs. Although these springs were small, and would realistically not provide a complete supply of water, the University was focused on acquiring as many sources available in the area as possible. In addition to pipes, the Board made plans to place cisterns around the Lawn to supply Pavilions, Hotels, student dorm rooms, and the Rotunda with water. The plans of the Lawn, done by Peter Maverick, depict the tentative locations of five cisterns; one behind each of Pavilions II, V, VIII, IX, and X (Figure 3).

Figure 3: “Plan of the University, from 1825” by Peter Maverick. The tentative locations of five cisterns are highlighted. Original housed in Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

A supplemental pamphlet, titled “Explanation of the ground plan of the University of Virginia,” acknowledges these “cisterns of fountain water, brought in [through] pipes from neighboring mountains.”[8] Originally published in 1822, Peter Maverick made the plan before construction of the University was completely finished.[9] Therefore, this plan is not valued for accurately depicting the location and number of cisterns actually built. Rather, it is valued for representing the overall intentions and thoughts of the Board of Visitors. Maverick made multiple copies of the plan, one of which has pencil markings labeled “drain” leading away from Pavilions V and VIII, as well as similar lines running along the southern side of the Lawn. These line markings appear to be the pipes referenced by the Board of Visitors in the February 26, 1819 meeting minutes and in the supplemental pamphlet for the ground plan.[10] The presence of the cisterns and the drawn-in pipes are an indication of the type of active and creative problem solving that combated the water supply problem.

In August, 1819, the University Proctor, Arthur S. Brockenbrough purchased lumber for creating the wooden pipes that would bring water from the spring atop the mountain on the west side of University grounds to the main buildings on the north east side.[11] Digging commenced in August 1819 to lay the network of pipes, which crossed Mr. Perry’s land in order to connect the water source to the main buildings. This work was difficult and required blowing through rocks; however, the pipes were the best option for getting water given the awkward split of the University’s land into two distinct sections. In a letter to Brockenbrough, James Wade suggests placing reservoirs made of oak plank that would hold thirty to forty gallons of water as high up as possible. Taking advantage of gravity, the water would flow without the use of costly pumps, and according to Wade, “in case of fire the water would flow freely.”[12] These reservoirs were supposed to last thirty years or more, a major investment that demonstrated another attempt at securing a long-term source of water.

After almost six years of planning and construction, the first faculty and class of students arrived to the still unfinished University of Virginia in the spring of 1825. With the system of pipes, cisterns, and rainwater collection for supplying water already in place, multiple flaws soon became glaringly apparent. Classes began in March 1825, and by April of that year, Jefferson felt pressure to secure a more plentiful water source for the school.[13] In an anxious letter to John Cabell, dated April 15, 1825, Jefferson shares an offer made to him by Mr. Perry to purchase the 132-acre stretch of land that separated the original two plots owned by the University.[14] This land would be valuable not only in uniting the Grounds, but in providing access to a “very bold spring, which might be brought by a small ditch so near the buildings of the University as to be of common use.” It is probable that this spring was one of the four originally referenced by Mr. Perry in his letter to the Board of Visitors in 1819.

The source of Jefferson’s anxiety and urgency became clear when he revealed that Mr. Perry was very motivated to sell. Perry was prepared to divide the land into smaller lots to facilitate sales, in which case the young University could not have afforded to buy the entire 132-acre portion. At $50 per acre, the land was by no means cheap, but Jefferson was willing to find the funds, confident that this fresh water spring would ensure “the most abundant supply of that element forever.”[15] A subsequent series of creative budget manipulations confirmed Jefferson’s claim that the purchase was within the University’s means. He planned to borrow the $3,000 down payment from the Rotunda fund, and student fees accounted for the rest of the payments. Jefferson’s willingness to transfer money from the Rotunda fund to improve water supply clearly indicates his fervent dedication to the University’s long-term success. His ultimate goal was to make the University a livable and desirable place to study, and a consistent source of water was a vital part of bringing his dream to fruition.

Jefferson took many risks and made difficult sacrifices in order to secure Mr. Perry’s land. His payment plan relied upon the enrollment of more than one hundred students in the second term, and he borrowed money from the Rotunda fund, which would set back progress on the centerpiece of the Lawn. The young and controversial University did not have guaranteed matriculation, making Jefferson’s plan particularly bold. He also skirted the Board of Visitor’s approval by indirectly purchasing the land through Proctor Brockenbrough.[16] On May 9, 1825, not even one month after Jefferson’s letter to Cabell, Brockenbrough purchased the 132 acres from Mr. Perry for $6,600.93.[17] Jefferson was taking a considerable risk by not waiting for the Board’s approval or securing the funds to reimburse Brockenbrough. Fortunately, the Board of Visitors approved the plan to purchase the desirable plot of land six months later, on October 3, 1825, only leaving the question of how to finance the major purchase.[18]

Four days later after the Board approved the plan Jefferson attempted to remedy the financial situation by requesting funds for reimbursing Brockenbrough from the President and Directors of the Literary Fund, the education fund for the state of Virginia.[19] Jefferson’s choice to borrow from the Rotunda fund and set back construction may have seemed unusual to the state. However, he made it clear that a secure water source was crucial if the institution was to remain open for years to come. After successfully securing the funds, Proctor Brockenbrough officially transferred the land deed to the University of Virginia on December 1, 1825, increasing the total area of land owned by the University to four hundred acres. Finally, Jefferson and the Board of Visitors secured what they considered to be a reliable and convenient source of water for the University of Virginia.[20]

The purchase of Mr. Perry’s land and subsequent fresh water springs was the early University’s last major effort to solve the water supply problem until the 1850s. In the years to come, the Board of Visitors faced other logistical challenges characteristic of a new institution, which often took precedence over water supply. This does not mean, however, that water was not still an issue to the students and faculty that were forced to endure the poor quality of its supply as fulltime residents at the University. While the Board of Visitors shifted major resources away from water and toward projects like the Rotunda, a series of minor efforts formed short-term solutions that placated the complaints of faculty members while temporarily addressing chronic water supply issues.

The wooden pipes meant to bring in water from surrounding streams and springs posed the greatest problems. The first evidence of an issue was in June 1825, only four months after the University opened, when Proctor Brockenbrough paid Mr. James Clark $10 for pipe and gutter repair on Grounds.[21] Complaints rarely cited a reason for repair, but a need for maintenance and repair so early on was cause for growing concern. The rot and deterioration only worsened as water saturated the wooden pipes. Jefferson himself made the next complaint in a letter to John Hartwell Cocke, written on May 20, 1826.[22] Jefferson regretfully informed Cocke of widespread rotting, saying “The pipes which bring water to the cisterns must be replaced. They have rotted from too shallow cover initially; no log should lye less than three feet deep.” He went on to admit that a solution would “cost more than [he] should be willing to risk in [his] own opinion, yet [he believed] it must be done and immediately.” Once again, Jefferson was willing to make the necessary sacrifice in order to obtain a solution to the costly and high maintenance system. He understood the relationship between a secure, reliable water source and a thriving University. Without consistent water supply, the quality of life at the University would be unacceptable, and the University would struggle to attract students and faculty, leading to failure.

Jefferson was determined not to lose his university to rotted pipes, and he was perhaps the most dedicated to solving the issue of water supply. Other members of the Board of Visitors were unable to see the link between water supply and the young University’s success as clearly as Jefferson did. After Jefferson’s death in July 1826, all complaints about the water supply at the University passed from one committee to another, usually with little progress made toward tangible improvements. This process was most frustrating for the faculty, who endured the consequences of living with a less than satisfactory water supply. As a result, tensions mounted between the faculty and members of the Board. The first record of faculty dissatisfaction was from a meeting on August 18, 1826. Faculty members requested that “the proctor arrange for a clean and complete supply of water.” [23] This grievance speaks to the severity of the problem, revealing that the supply of water was so diminutive and so unsanitary that faculty members felt moved to lodge a complaint. Water supply had never been profuse, but the demands of faculty and student life exposed the extent of the water deficit. Additionally, the pipe system had no filtration component, so any water that did travel through the pipes contained any sediment or dirt present at the original source. The insufficient supply of water likely contributed to the tension between the professors and the Board of Visitors.

Diffusion of responsibility among faculty members, the proctor and the Board of Visitors, discouraged cooperation and obstructed definitive improvements to the overall water supply system. The Faculty Committee made a recommendation on September 9, 1826 that the Board of Visitors divert all issues of water supply to the proctor.[24] However, Proctor Brockenbrough passed the issue to the Board of Visitors in a letter dated October 1, 1826.[25] The issue was “referred to the executive committee to be acted upon according to their discretion,” meaning the Board of Visitors itself was responsible for devising a solution. This vague plan allowed the Board of Visitors to all but ignore the faculty’s protest, with no moves toward tangible progress.[26] During the first year of the University’s existence, it was unclear exactly who was liable for maintaining the water system. The University deferred issues of maintaining the internal, external, and gardens of Pavilions to the professors who lived in them.[27] Therefore, it is likely that professors were initially responsible for maintaining aspects of the water supply system on their property, for example, those living in pavilions with cisterns in their gardens. Leaving faculty members individually accountable for small portions of the water supply system, universal improvements would have been near impossible.

Over the next twenty-five years, cooperation did not improve and complaints to the Board of Visitors continued, requesting that pipes be repaired, cisterns enlarged, or roof collection systems be mended. Occasionally, a member suggested a more creative and long-term solution, but such recommendations were rare. Signs of change emerged in July 1839, when the Board of Visitors requested that Professor Bonnycastle and Professor Davis calculate the cost and develop a plan for replacing the wooden pipes with an iron network.[28] On July 1, 1845, the Board considered the cost of laying additional pipes from the spring on the university’s mountain, with the contingency plan of constructing additional cisterns in the event that piping would be too expensive.[29] Although neither plan was implemented, suggestions of major improvements show a welcomed return to thoughts towards enduring solutions. The faculty even attempted to take matters into their own hands by appointing a committee dedicated to overseeing water supply in 1853.[30] Unfortunately, the early University probably did not have the funds to undertake the major projects proposed, so the problems persisted.

After a quarter century of minor solutions that only gave short-term relief to the University’s water problem, the Board of Visitors made a major effort to end the problems permanently. The Board of Visitors planned to replace the entire outdated wooden pipe system with a new network of iron and lead pipes. These new pipes would supposedly be resistant to the rotting and leaking problems that plagued the wooden pipes since the beginning. The timing of this project is not coincidental. From 1842 to 1853, the student body almost quadrupled in size, increasing from 128 to 465 students.[31] The growing social and political tension between the north and south leading up to the Civil War lead to the increase in attendance in the 1850s. The University of Virginia grew in popularity among southern families who were seeking to educate their sons and unwilling to send them to northern schools. It is likely that the University outgrew the old system of supplying water and desperately needed something more reliable and efficient to replace it.

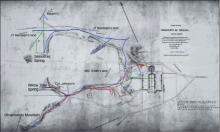

Finally, the University attained the funds to make the necessary improvements. In June 1855, the public Treasury of Virginia granted the University of Virginia $25,000 for repairing the terraces and water supply system.[32] Of this grant, the University allocated $15,000 solely to improving the water system. The Board of Visitors first sought the opinion of engineer F. Eardman of Philadelphia, and several other engineers submitted plans, but it was clear early on that the University could accept none of the proposals due to financial restrictions.[33] All the plans offered exceeded the total budget of $25,000. Even so, none of the plans would have been possible without the cooperation of the owner of a spring that was vital to the functioning of almost all possible plans. Determined to find a feasible plan, the Board of Visitors hired engineer Charles Ellet Jr., on June 24, 1856, to develop a new way of supplying water to the university.[34] Ellet worked with Mr. S. A. Richardson to survey the University’s land and draw up a map of the existing water supply system including all the pipes, cisterns, and water sources. It appears that the University did not make any improvements to the system, and on February 13, 1857, Ellet and Richardson were paid $300 and $154.38 respectively by the University for their work.[35] Realizing the urgency of the problem, the Board of Visitors hired Ellet once again in June 1857 to “have the additional surveys for water made by Mr. Ellet at the earliest practicable time and that [the Board] be authorized and instructed to contract for the execution of the works, as soon as possible.”[36] In September of the following year, the Board of Visitors acted with impressive motivation and productivity. They approved Ellet’s second plan for improvements and sought to implement them as soon as possible (Figure 4).[37] At last, relief from the tiresome wooden water system was in sight for suffering students and professors. The plan implemented was complicated; it involved numerous additions to the previous network, took advantage of additional springs, and provided more widespread access to water across Grounds.

Figure 4: Charles Ellet’s (1856a) “A Map of the University of Virginia and it’s Vicinity.” Edited by Stephen M. Thompson, Rivanna Archeological Services. Original housed in Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

In Ellet’s plan, the blue, green and red lines represent the possible paths that new pipelines could take. All the options presented take advantage of the springs on University Mountain and a small pond near the University cemetery. The system also takes water from Willow Tree Spring near Colonel Johnson’s home near University Mountain and Sassafras Spring to the north. Ellet’s system relied on the use of pumps to transport water from various sources around the University directly to the buildings on the Lawn, which solved volume and pressure problems, but increased the likelihood of mechanical repairs. Ellet’s system was by no means perfect; nonetheless, it was a major upgrade for the University. The gesture of such an expensive and extensive renovation indicated a sense of responsibility and caring on the part of the University. The Board of Visitors made long anticipated steps toward fixing the leaky pipes, dry-spells, inadequate reservoirs, and dirty water that frustrated professors and students from the beginning. While problems eventually emerged with the new system for decades to come, the large-scale project of Ellet’s renovation was the last major improvement made during the antebellum period.

Overall, the proximity of the University to natural water sources made finding a supply time consuming and costly, ultimately taking years to secure. The story of water at the early University of Virginia provides insight into many aspects of the early university, including the importance of natural resources for sustaining a large institution, the Board of Visitors' process for budgeting renovations and repairs, and the working relationship between the faculty, proctor, and Board. The variety of solutions and approaches the Board took to solve the water supply problem revealed the complexity of finding the necessary water where natural resources were scarce.

[1] Thomas Jefferson, “Thomas Jefferson to Joseph Priestly,” Jefferson Quotes and Family Letters, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, http://tjrs.monticello.org/letter/1744

[2] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, February 26, 1819, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[3] Lands of Central College [map], 1819. Scale not given. University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[4] "Historical Society Library." Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. Accessed April 22, 2015. http://albemarlehistory.org/index.php/library_maps.

[5] Catalogue of the officers and students of the University of Virginia. First session, March 7th, 1825-December 15th, 1825, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[6] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, February 26, 1819, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[7] James Dinsmore and John M. Perry to the Board of Visitors, 1819 March 27, Jefferson Papers of the University of Virginia, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[8] Explanations of the ground plan of the University of Virginia, 1824, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[9] Peter Maverick. University of Virginia (Ground Plan) [map]. 1822. Scale not given. “University of Virginia Online Exhibits”. http://explore.lib.virginia.edu/items/show/214. (March 29, 2015)

[10] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, February 26, 1819, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[11] George Spooner to A. S. Brockenbrough Aug. 20, 1819, Papers of the Proctors of the University of Virginia, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[12] James Wade to A. S. Brockenbrough Oct 7, 1819, Papers of the Proctors of the University of Virginia, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[13] Cabell, Nathaniel Francis, and Thomas Jefferson. Early History of the University of Virginia. Richmond, Va.: J.W. Randolph, 1856. 348.

[14] Cabell, Nathaniel Francis, and Thomas Jefferson. Early History of the University of Virginia, 348

[15] Cabell, Nathaniel Francis, and Thomas Jefferson. Early History of the University of Virginia, 348

[16] Deed of land transfer from John M. Perry to A. S. Brockenbrough, May 9, 1825, Papers Relating to Land Belonging to the University of Virginia, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[17] Deed of land transfer from John M. Perry to A. S. Brockenbrough, May 9, 1825, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[18] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, October 3, 1825, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[19] Cabell, Nathaniel Francis, and Thomas Jefferson. Early History of the University of Virginia. Richmond, Va.: J.W. Randolph, 1856. 485.

[20] Deed of land transfer from A. S. Brockenbrough to the Rector and Board of Visitors, December 1, 1825, Papers Relating to Land Belonging to the University of Virginia, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[21] Brockenbrough receipt record, June 5, 1825, University of Virginia receipt book kept by proctor Arthur S. Brockenbrough, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[22]Thomas Jefferson to John Hartwell Cocke, May 20, 1826, Thomas Jefferson letters to General Harwell Cocke, and other items, 1742-1826, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[23] Faculty Meeting minutes, August 18, 1826, University of Virginia faculty papers [manuscript] 1853-1960, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[24] Report of the Faculty Committee for General Purposes to the Board of Visitors, September 9, 1826, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[25] A. S. Brockenbrough to the Board of Visitors, Oct 1, 1826, A. S. Brockenbrough letters to the Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[26] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, October 2, 1826, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[27] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, April 5, 1824, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[28] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, July 3, 1839, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[29] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, July 1, 1845, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[30] Faculty Meeting minutes, October 17, 1853, University of Virginia faculty papers [manuscript] 1853-1960, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[31] Catalog of the University of Virginia, 1842 and 1853, UVa text collection Catalog of the University of Virginia, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[32] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, June 26, 1854, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[33] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, June 26, 1855, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[34] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, June 24, 1856, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[35] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, February 13, 1857, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[36] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, June 25, 1857, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.

[37] University of Virginia, Board of Visitors, September 1, 1858, UVa text collection UVa board of visitors minutes, 1817-2002, University of Virginia Library Special Collections, Charlottesville.