FRAGMENTS: PARTIALLY DOCUMENTED PERSONS AND EVENTS

Julia Munro

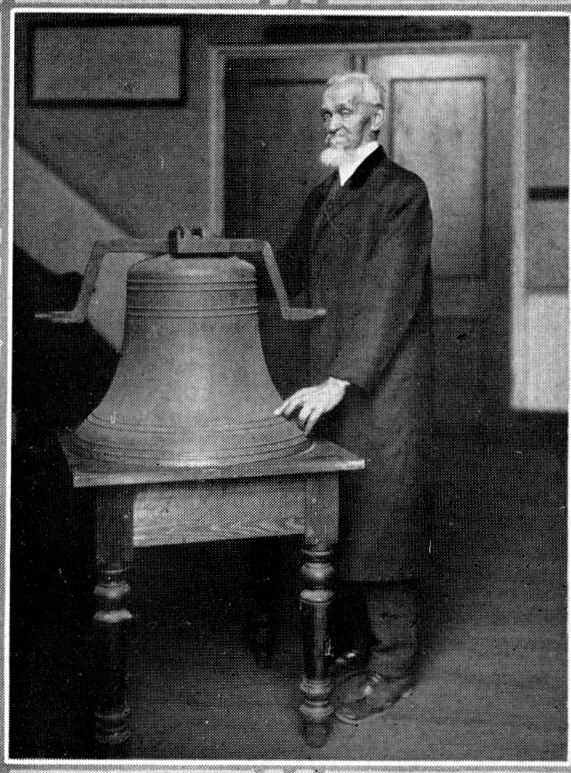

Portrait of Henry Martin [P46982] Former Slave and Bell-Ringer at University of Virginia

This section provides fragments of recorded experiences, fragments being near-exclusively all that was recorded about the lives and events of enslaved individuals in the antebellum era. We provide here these fragments, as fleshed out as best we can, in order to rightfully document and make known the important presence of the enslaved in the building and support of Jefferson's university. We frequently work against an absence of unique/full names, birth dates, lineage, family, and place, and work with what the records did provide - names of slaveowners, overseers, leasers, heads of households - in order to provide proof, as accurately as possible, of the Black histories that are inseparable from the University of Virginia's history, if heretofore minimized.

Click here[1] to jump directly to Fragments.

Along with the fragmentary nature of identifying information and the sparse nature of records that mention slaves, the way in which the University of Virginia functioned in relation to slavery also presents difficulty to researchers today. In a rhetorical move typical to the antebellum period, the University-as-slaveholder renders itself invisible in the master/slave relationship through the careful wording of transactions, enactments, minutes, bills of sale, and other records. In short, the act of slaveholding, of ownership, is elided. Consider, for instance, the wording of the resolutions from the Board of Visitor Minutes of July 4, 1840:

"17. Resolved that it shall be the duty of the Librarian to cause the floor of the Hall and galleries of the Library to be scoured . . . as may be necessary to keep them in a clean & neat condition; and that he be authorised to call upon the Proctor for the hirelings of the University to perform that service.

18. Resolved, that it shall be the duty of the Librarian to cause the hall and galleries of the Library to be swept once every day, & that he shall be authorised to employ the servant who attends at the Rotunda and rings the Bell to perform this service."

Amidst these indirect declarations, passed from one official to another (Librarian to Proctor), can be gleaned the person or persons ("the servant," "the hirelings") who performed such actions (the performance of X service). And, although minimal in detail, such references can be traced throughout the Board of Visitor Minutes and other University documents in order to unearth the person, his or her actions, and his or her impact upon the university. The servant who "rings the Bell," for instance, we know of through other records that discuss his duties, and thus can add more detail to his history and his part of Jefferson's University. Should no more references be traceable, at the least we are able to bring to light "the hirelings" of the University, and thus to acknowledge their contributions.

Engravings of the Academical Village: A Symbol of Hidden History

Perhaps most emblematic of this largely overlooked history is one engraving of many of the Academical Village: one so similar in appearance as the others and yet so markedly different, in its near-hidden depiction of a black woman. To view the illustrations discussed below, please visit the "Engravings of the Academical Village" Image Gallery (additionally, see the University of Virginia library's online guide to the "Edwin M. Betts Memorial Collection of University of Virginia Prints, Photographs and Ilustrations 1817-1930").

Common to nineteenth-century pictorial conventions, engravings of the Academical Village throughout the 1800's appear generic to one another, despite slight picturesque variations (a change in elevation, the addition or manipulation of buildings or figures, human and animal, to the scene). While such variations and consistencies - the nearly identical scene being reproduced from one illustration to another - may seem antithetical to present notions of documentation, such image conventions were not abnormal in the use of illustration as an objective documentation of events and environments (certainly prior to the invention of photography in 1839 and arguably through to the late 1800s, when actual photographs could be reliably reproduced and widely disseminated via newspapers).

The body of Academical Village illustrations of the 1800's - some twenty-five specimens - can nonetheless provide information about the actual construction and renovation of the buildings of Jefferson's Village, while also providing telling information about the cultural/societal periods in which they were produced. Some illustrations, for example, depict the Lawn as an empty, if not perfectly manicured and serene, space. Others (such as the background image of the JUEL web site) include groupings of figures that, if generic, nonetheless signal the environment of the Village: young male students in conversation; well-dressed gentlewomen, attended by gentlemen, in a sightseeing of the Village architecture, a jaunty dog or two traversing the Lawn, a figure with a basket.

One illustration alone, however, contains a grouping that is unique despite its being so very generic: a Black Woman with Child. They are depicted by B. Tanner in an illustration of the Village that was included as part of the Herman Böÿe 1826 map of Virginia. As can be seen in the image below, it is typically conventional in its depiction of the Village and the individuals therein. Unlike other such illustrations of the Academical Village, however, B. Tanner chose to include the figure of a black woman holding a child, a small but significant addition in the left-hand foreground of the image:

It is a depiction that would have been instantly familiar to the nineteenth-century viewer: a black woman, slave/servant/nurse to the white child, dark skin and nondescript dress made all the more stark of a contrast to the innocent white of the child's garments and complexion. Such a figural depiction would have been familiar to the 1820's viewer due to its continued repetition in media of his time period and much, much earlier: a seeming perversion of the Madonna and Child, depicted in adverts, periodical literature (magazines, newspapers), ballads, political pieces (including those for and against Abolition), fine art, fiction, blasphemous materials, and so on.

Indeed, the woman and child in B. Tanner's engraving seem to function in a documentary manner: a grouping that, along with other typical figures he depicts, purports to show the life of the Academical Village. The woman and child may have actually been there while he originally created the image, or not. As depicted, she does not seem to evoke a particular stereotype of a Black Woman, which would most obviously be revealed in the artist's choosing to depict her face in the conventional manner, with wildly-exaggerated facial features. That B. Tanner avoids this choice by literally drawing a blank black face would seem significant, if it were not for the fact that other figures within the image also have blank faces. Nonetheless, her presence as depicted - white child in arms - cannot help but evoke the visual references outlined above for the ninteenth-century viewer: in short, images of an individual black person were inescapably overdetermined by culturally-laden stereotypes of the Black Person.

However conventional the black woman may appear and however she may be read by her contemporary viewers, her presence in B. Tanner's engraving is ultimately of most significance to our understanding of Jefferson's university in that it renders visible the Black Presence in the Academical Village. Indeed, her being there and being visualized can be seen as symbolic of the history of African Americans as part of the history of the University of Virginia: although nearly obscured and vaguely traced, the information regarding black invididuals is present and visible in the documents and records of the University, if only one looks closely. "Fragments" provides here these traces.

[1] FRAGMENTS

1. Chairman's Journal, March 3, 1836

"I was informed to day by Mr. Penci (P43877) that the servants in the University are in the habit of furnishing expensive suppers to the students; & that a small negro boy (P46981) who is often going about selling apples to the students, frequently carries breakfast to their rooms, in his covered basket, which I supposed contained nothing but apples. This boy belonging to no one in the University, but living with a free woman (P44621), the wife of Dr. Magill's (P43655) servant (P44622), in the basement of Mr. Roger's (P43658) house [Pavilion VI, PL8458], I had him sent out of the University immediately. And I requested that the Professors whose servants, as I learned, had been in the habit of furnishing suppers & to interpose their authority to prevent continuance of the practice."

Note: No further information has of yet been found regarding this specific boy, nor the free woman and her husband, Dr. Alfred Thurston's Magill's servant - partly due to the confused terms by which the brief situation is described. The boy is said to live with the free woman in the basement of Professor William Roger's house, Pavilion VI; it is not specified where her husband lives. Dr. Magill at the time lived in Pavilion III (PL8446). What is interesting is that the "status" of each individual is specified: a boy not belonging to the University, a free woman, and a servant.

2. Chairman's Journal, February 17, 1836

"Today on examining a basket which one of Mr. Conway's servants was bringing into the University, I found two bottles, one of rum, and the other of whiskey, which he said were for himself. I have no doubt that the rum at least, and most probably the whiskey also, were for students. The Proctor, whom I informed of the circumstance and requested occasionally to examine the baskets brought by the servants into the University, reported to me in the evening, that he had just detected two of Mrs. Gray's servants, one bringing into the University a bottle of rum and the other a bottle of wine; which they stated to be for themselves. As, if the Hotel servants are allowed to bring spirituous or vinous liquors within the precincts for themselves, they will whenever detected bringing them for students say they are for themselves, it is necessary that they shall be prohibited from bringing them at all. And as we cannot well enforce the prohibition by action against the servants themselves, we must in some manner make the master responsible for its violation. I shall therefore propose to the Faculty, to pass a resolution declaring that if any Hotel servant shall bring within the precincts any vinous or spirituous liquors, except by the order of his master, or shall have any such liquors within the precincts, the Hotelkeeper will be required immediately to dismiss him from the University."

Note: This passage does not focus in much detail on the particular servant of Mr. Conway's (P43888), but does discuss in general the status of hotel servants: here, mentioning Hotelkeeper Edwin Conway's servants at Hotel A (PL8432), and Mrs. Sarah Gray's (P43865) servants at Hotel E (PL8436).

3. Chairman's Journal, April 16, 1828 and Enactments, 1825

"The Proctor was requested to see that all servants hired by students should be sent away from the Precincts, particularly, a boy named German [P44620]."

Note: This single sentence, although brief, captures the indirect language used in reference to slavery and the University's role: although not directly named, the University nonetheless directs the presence of slaves on campus by passing responsibilities and direct interactions with slaves to individuals of the academical village: in this instance (and, in most instances), the Proctor. It also states the University's stance that students were not allowed to hire or bring from home their own personal servants, as is stated in the Enactments by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, 1825: "No student shall, within the precincts of the University, intro- duce, keep, or use any spirituous or vinous liquors, keep or use weapons or arms of any kind, or gun-powder, keep a servant, horse or dog,. . ."

4. Chairman's Journal, May 6, 1832

"Jack Kennedy [P44969], a mulatto man, having applied for one of the cellar rooms for a barber's shop for the accommodation of students" was said to have been approved by the Proctor, who deemed the shop a good way to keep students out of town (and, out of mischief), although such "grant could be revoked at pleasure," and must not aid sutdents in violation of the enactments.